First Contacts!

By Flt/Lt Gary Weightman

Part 1:

The Big Stick and the Looped Hose.

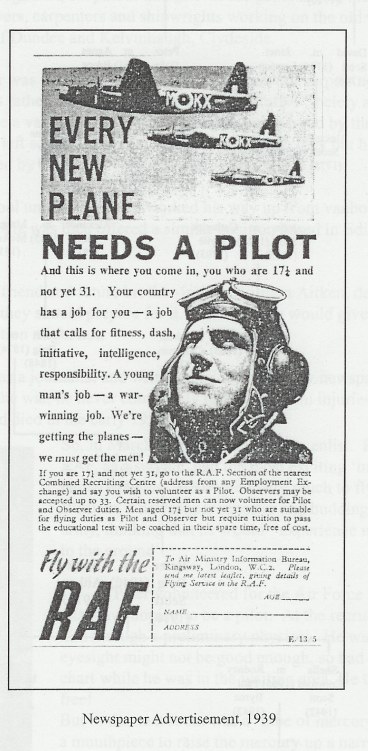

As the air war over the Balkans demonstrates once again, the effective application of global airpower is highly dependant on air to air refuelling support provided by the fleets of NATO tanker aircraft that crowded airfields from Brize Norton to Budapest. AAR has been a vital factor in air warfare since Korea and Vietnam and the RAF tanker force has played a major role in campaigns from the Falklands to Iraq and Yugoslavia. However, despite the invention of practical AAR in Britain it was the United States and the USAF that first took up the technology and applied it to military use. It was fifty years ago that AAR evolved from a flying circus stunt into a military force multiplier. This major development in aviation took place in the skies over Southern England in 1949 and it is important to mark the 50th anniversary of this historic event. It is a story full of political intrigue, inter-service rivalry, bureaucratic obstruction and heroic British innovation.

The birth of the United States Air Force on 18th September 1947 had not been an easy one. The US Navy, who feared that they would lose control of their own aircraft, had opposed its formation at every stage. The advent of atomic weapons added a new twist to this bitter inter-service rivalry. The USAF argued that it had the sole means of delivery of the atomic bomb in its long range strategic bomber force and should receive the lion's share of defence funding to pay for its new B-36 bombers. The Navy were appalled at the possibility of losing out and argued that the USAF had misled congress on the B-36's performance and that billions of dollars would be wasted. These dollars would be better spent on new 70,000-ton supercarrier, the USS United States, that could carry a 45-ton atomic bomber and be capable of striking from the sea at an enemy anywhere in the world. When the Russians blockaded Berlin on 31st March 1948 it became clear that this enemy would likely be the Soviet Union.

Footnote to Garys comment regarding the Soviet Union. Some readers may not be aware but Churchill, in an absurd lack of foresight or blatent arrogance, put all of the Western worlds Atomic science on the table during negotiations with Stalin. A stroke of bureaucratic lunacy indefensible and beyond all comprehension. "Nothing like starting a nuclear arms race on an even playing field".What helped Churchill win some token concessions from the Russians would nearly cost us the planet in years to come.

The USAF was rattled by the Navy's case. Their existing B-29 bomber didn't have the range to reach targets in central Russia and the giant B-36 was proving to be a sluggard in early trials. The Boeing B-47 and B-52 jet bombers were years from entering service and the Navy were clearly ahead in the game. The USAF could only win the nuclear funding battle if they could prove that their Strategic Air Command bombers were capable of reaching their targets from bases in the USA. The solution to the problem appeared to lie in the hands of a small company based in Dorset, England.

Flight Refuelling Ltd had been formed by British aviation pioneer Sir Alan Cobham in 1934 to develop air to air refuelling as a commercial proposition. By 1939 the first regular flight refuelled transatlantic airmail flights, using the looped hose method, were inaugurated but the outbreak of war terminated the service. The surplus equipment was used in a series of successful wartime trials in the USA and in 1944 Sir Alan was awarded an air ministry contract for 600 sets of looped hose flight-refuelling equipment for the RAF's "Tiger Force" Lancasters. A considerable amount of work had been completed before the contract was suddenly cancelled in 1945. After the war Flight Refuelling continued the transatlantic trials leading to a successful flight refuelled passenger service to Bermuda in 1947

When the success of these trials came to the attention of the USAF they decided to adopt the procedure themselves. In April 1948 a group of senior USAF officers arrived at Flight Refuelling Ltd's Tarrant Rushton base with an immediate order for 40 sets of their "looped hose" equipment (later extended to 100). Fortunately, Sir Alan Cobham had just purchased at scrap value from the Air Ministry all the parts and components produced for the "Tiger Force" tankers and receivers and could easily meet the tight delivery schedule set by the Americans. Boeing began a rapid conversion program that would eventually produce 92 KB29M "looped hose" tankers and 131 B29 and B50 receivers. The first B-36A entered service with SAC in June 1948 and work began to convert the giant bomber into a looped hose receiver. By December 1948 the USAF was ready to try out the system.

The political battle with the US Navy was approaching a climax with a congressional inquiry into the conflicting merits of the B-36 mega-bomber and the USS United States super-carrier. The USAF needed some positive publicity and the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour gave them a perfect opportunity. On the 7th December 1948 a B-50 bomber flew from Carswell AFB, Fort Worth, Texas, carried out an undetected mock attack on the US Navy's Pacific fleet in Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, dropped a dummy 10,000lb atomic bomb and returned, completing a round trip of 9,400 miles using looped hose flight-refuelling. Much to the chagrin of the US Navy, this demonstrated the vulnerability of their fleet bases to atomic attack by long-range bombers and greatly assisted the case for SAC and the B-36.

To further demonstrate its new global strike capability the USAF planned the ultimate in long-range record attempts, to fly non-stop around the world. On Saturday the 26th February 1949 a Boeing B-50 named "Lucky Lady II", of the 43rd Bomb Group, departed from Carswell AFB and flew 3,800 miles east towards the Azores. At Lages 4 KB-29M tankers waited and 2 were used for the first refuelling. Lucky Lady II then flew 5,200 miles to Dhahran for a second bracket, 4,900 miles to the Philippines for the third and 5,300 to Hawaii for a final refuelling before landing at Fort Worth on Wednesday 2nd March. The flight covered 23,452 miles and took 94 hours and 1 minute. In all, 16 KB-29M tankers of the 43rd Air Refuelling Squadron were deployed along the route, an indication of the rapid build-up of the USAF tanker force just 10 months after the contract was signed with Flight Refuelling Ltd. The around-the-world flight was final proof that the US Air Force bombers were capable of striking anywhere in the world. The USAF won its case for the B-36 in congress. Although construction had already begun on the USS United States it was cancelled in April 1949. Efforts by the Navy to blacken the name of the B-36 and even hint at corruption in high places failed to reverse the decision and the bomber went on to be the mainstay of SAC's nuclear "big stick" in the early 1950s.

Part 2:

Dustbin lids, Roller Blinds and Relief Tubes.

Despite Cobham's continuing belief that his flight-refuelling system had a future in commercial aviation it was the military that now drove developments and the USAF, rather than the RAF, its main proponent. Although Flight Refuelling's looped hose method was a proven and reliable system its complexity and the low speed required for the operation limited its use to large multi-crew piston-engine aircraft. In 1947 the Air Ministry had concluded that the system was impractical and of little value in future military operations and that any further development of flight-refuelling equipment would be discontinued. Had it not been for Cobham's persistence and the lucrative USAF contract development in Britain might have ceased altogether. In the USA Boeing began investigating the "boom" method for refuelling high speed jet bombers but the USAF were also interested in any new AAR technique that could be used for single seat jet fighters. Cobham had been told of this interest late in 1948 during a lunch with senior USAF officers at Wright Patterson AFB, in Dayton, Ohio. He rashly mentioned that his company was already working on such a system. The USAF generals were most impressed and arranged to visit Flight Refuelling Ltd's Tarrant Rushton base in the spring of 1949 for a demonstration. Unfortunately, Sir Alan had been bluffing and no such project yet existed. The "looped hose" method had taken many years to develop and now he had just over 4 months to come up with a completely new system.

Returning to England Cobham gave the new project top priority with his design team. Several options were investigated before attention began to centre on a receiver aircraft equipped with a probe mounted nozzle which would make contact with a receptor coupling in a tapered funnel or drogue on the end of a tanker's hose. Various designs of drogue were tested by towing them at high speed behind a car down the runway at Tarrant Rushton. In principle the technique looked promising but a problem remained on how to prevent the tanker hose from whipping and looping when contact was made. It was Flight Refuelling engineer Peter Macgregor who came up with the solution. He considered the method of retraction used by measuring tapes and roller blinds while lying in bed one Sunday morning. If a spring could take up the slack then the problem of hose whipping would be eliminated. Macgregor decided that a mechanical spring system would be too heavy but design work showed that an electro-hydraulic fluid drive motor attached to a hose drum unit would do the job and could be fitted in one of Flight Refuelling's Avro Lancaster tankers. All that had to be found was a suitable receiver aircraft.

Cobham was a master at getting results from an unenthusiastic Air Ministry and eventually Meteor Mk 3 EE397 was loaned by the RAF to the company for the trials. Time was running out and Flight Refuelling had just over a month to refine the coupling system and modify the Meteor with a nose-mounted probe and internal fuel lines. The system was eventually ready for the first flight trials just two days before USAF General Carroll and his team were due to see a demonstration of the new probe and drogue technique.

On Saturday the 4th April 1949 FRL's test pilot Pat Hornidge took off from Tarrant Rushton in Meteor EE397 and carried out the first series of dry contacts with the Lancaster tanker flown by Tom Marks. Throughout the weekend flight trials sufficiently refined the technique of the probe and drogue tanking to allow the planned demonstration to take place promptly at 10.00 am on Monday when the USAF officers arrived. Not only had a completely new method of AAR been developed in a matter of months, but also for the first time a jet aircraft had refuelled in flight, which heralded a new era of possibilities. The USAF delegation was most impressed with the demonstration but technical problems delayed a repeat performance for over a month. Eventually a series of seven demonstration flights were planned for VIPs from the RAF and aviation industry. Sir Alan claimed that his probe and drogue system could transfer fuel at 4,000lbs a minute while flying at 400kts at 35,000ft. However, one officer noted that the demonstrations were restricted to contacts at 130kts and 2,000ft and little fuel appeared to be transferred to the Meteor. Cobham managed to convince the sceptic that a temporary snag had curtailed that particular demonstration but in truth unless his company acquired a more capable tanker than the Lancaster from a reluctant Air Ministry it would be difficult to carry out any high altitude trials.

To dramatically demonstrate the operational advantages offered by the probe and drogue method, test pilots Hornidge and Marks organised an attempt on the world jet endurance record. On the 7th August 1949 Hornidge took off from Tarrant Rushton in the Meteor and flew a continuous circuit down the Bristol Channel and along the south coast to the Needles to rendezvous with Mark's Lancaster orbiting around the Isle of Wight. Hornidge remained airborne for 12 hours and 3 minutes flying about 3,600 miles. He made 10 refuelling contacts and received a total of 2,352 imperial gallons of kerosene. During his record flight he suffered the indignity of a "pee tube" failure, which flooded his cockpit floor, but the attempt was a great success and gained considerable international publicity for FRL's revolutional new probe and drogue AAR technique.

1949 also saw the first deployment of USAF tankers to the UK when the KB-29Ms of the 43rd Air Refuelling Sqn deployed to RAF Marham to carry out looped hose AAR exercises with B-50 bombers based in East Anglia. The old method was having mixed results in service with the USAF and by the end of the year the arrival at Tarrant Rushton of four B-29 bombers for conversion to HDU equipped tankers showed the way ahead. One of the aircraft would be converted into the world's first 3-point tanker, designated YKB-29T with Mk 11 HDUs mounted in the bomb bay and on each wingtip.

It is 50 years since the momentous events of 1949 but the year truly marked the birth of military AAR with the British invention (backed by American money) of the probe and drogue technique. The USAF used probe and drogue in TAC until the Vietnam War before standardising on the SAC fleet of boom equipped KC-135 tankers. The reintroduction of hoses on USAF tankers in recent years may indicate the error of the earlier decision. The RAF was slow to adopt AAR and it was not until November 1959 that No 214 Sqn became the RAF's first fully operational tanker unit equipped with single-hose Vickers Valiants. It was 1966 before the first 3-point Victor tanker entered service with No 57 Sqn. However, probe and drogue has proved to be the most versatile method of AAR, capable of use with aircraft as diverse as helicopters and supersonic fighters and it enables even the diminutive A-4 Skyhawk to be used as a tanker. Its invention is most worthy of celebration on its 50th anniversary year, so let's raise our glasses to Cobham, Macgregor and roller blinds everywhere! Cheers!

Part 3:

Bust and Boom.

The triumphant British invention of the world's first practical in-flight refuelling system in 1949 can, with hindsight, be seen as a major milestone in the development of airpower. Indeed it can be argued that the development of probe and drogue rivals that of the jet engine in the UK's contribution to modern aviation. Yet far from bringing glory and profit for Flight Refuelling Ltd the technology continued to be regarded as an unnecessary circus stunt by the mandarins of the Air Ministry and by the end of the year the firm faced bankruptcy. Of even more concern was that the small Dorset based company now found itself in direct competition with the most powerful aviation industrial complex on the planet, Boeing!

The unenthusiastic attitude of the Air Ministry was very much a symptom of the time. Money for research and development in Post war Britain was almost non-existent. Even Whittle's company, Power Jets, was wound up, as the government appeared more willing to give away jet technology to the Americans and Russians rather than develop it at home. What funds existed were poured by beauracrats into dead-end prestige projects such as the Bristol Brabazon long-range airliner. The successful trans-Atlantic in-flight refuelling trials of 1947 appeared irrelevant if an aircraft could be built to cross the ocean on internal fuel alone. The Air Ministry had already concluded that "flight refuelling on future types of aircraft is not a paying proposition.it is not proposed to continue any further development.but to rely on the aircraft carrying internal fuel for the ranges required." The difference in opinion between the British and Americans over the advantages of AAR could be explained by the very different wartime experiences of their air forces. The RAF had fought mainly in the European theatre over what would be considered today as tactical ranges. Lancasters, Lincolns and even Mosquitoes could easily reach their targets in Eastern Europe from bases in England and aircraft under development promised even greater ranges. However, the USAAF 20th Air Force had fought their campaign in the Pacific over ranges unimagined a few years earlier. It is 635 miles from Brize Norton to Berlin but the USAAF B-29 Superforts had been flying 3128-mile round trips from Guam to Tokyo. This vast difference in experience may partly explain why the British were reluctant and the Americans ready to embrace AAR.

However, profits from the successful looped-hose deal with the USAF barely covered losses incurred by Flight Refuelling when its Berlin airlift contracts were suddenly cancelled earlier than expected in August 1949. To save the company Cobham was forced to sell a majority shareholding to a merchant bank who promptly began an asset stripping operation. It is in these harsh financial conditions that we reach the next stage of our story. The arrival of 4 Boeing B-29 bombers and 2 Republic F-84 Thunderjet fighters at Tarrent Rushton for probe and drogue conversion.

Codenamed "Operation Layette" (later changed to "Operation Outing") this project represented a huge leap forward from the Lancaster/Meteor trials of the spring and summer of 1949. The first B-29 was fitted with a single Mk 8 HDU in the rear fuselage and two others were fitted with a probe extending forward above the cockpit for the first bomber trials with the new system. The single point tanker was redesignated the KB-29T and the receivers became B-29MRs. It had been intended that the B-29MRs would have a pneumatically powered "ejector probe" which, when selected by the pilot, would shoot out to make contact with the drogue. This exciting development was abandoned at the time as overcomplicated but has been born again in recent years for helicopter AAR.

The most significant conversion was made to the second B-29. This was fitted with 3 electrically driven Mk 11 HDUs, two of which were fitted in wing-tip pods, becoming the world's first three-point tanker, designated YKB-29T. Both F-84s were fitted with wing mounted probes, becoming EF-84Es in the USAF inventory. Unfortunately the Superfortress and Thunderjet were considerably more advanced and complex than the Lancaster and Meteor and the conversions proved to be far more difficult than expected. A fixed price contract had been agreed before Cobham's engineers had been able to see what work would be required and although the company was able to meet its commitment the costs overran significantly. With no sign of British government support and in order to cover his losses, Cobham was forced to sell the manufacturing rights for the probe and drogue system to the Americans, less than a year after its invention in the UK.

To add insult to injury Flight Refuelling Ltd also lost its effective monopoly in practical refuelling techniques. Boeing, who had benefited from FRL's work with huge USAF contracts to convert B-29s into KB-29M tankers, had been working in secret since November 1947 on a new in-flight refuelling method for its future swept-wing B-47 jet bomber. On the 19th October 1949 Boeing publicly revealed its "hitherto classified device", the flying boom refuelling system.

Boeing claimed several advantages of their new boom over probe and drogue. The rigid boom could allow a higher fuel flow than a hose. The boom could operate at greater altitudes and speeds than had been demonstrated with probe and drogue. Also, as a boom operator in the tanker aircraft made the coupling with the receiver, receiver pilots would not need to be trained in the formation skills required for probe and drogue contacts. The final advantage of the boom over probe and drogue in the eyes of America was that it was an invention of good old Yankee know-how and not some Limey lash-up.

Although many of the so-called advantages of the boom system were illusory the Boeing challenge threatened FRL's AAR lead with probe and drogue. As 1949 drew to a close the future adoption of the probe and drogue technique on a large scale by the USAF was still in doubt and interest from the RAF was non-existent. 1950 would be a make or break year for the system and the future of Flight Refuelling Ltd.

Part 4:

The "Tripple Nipple" goes to War.

At the beginning of 1950 in-flight refuelling was a well-established technique in the USAF. The first Air Refuelling Squadrons, the 43rd at Davis-Montham AFB in Arizona and the 509th at Roswell AFB in New Mexico, had been in business since June 1948 using the looped hose system and Boeing was making great progress with its flying boom tanker. FRL's probe and drogue had been proven as a system that could be used successfully by jet fighters and work was under way at Tarrent Rushton to convert two B-29 bombers to HDU tankers and fit more bombers and F-84 Thunderjet fighters with receiver probes. However, without British government support FRL's attempts to compete on equal terms with Boeing were doomed to failure. The conversion work on the American aircraft was much more complex than anticipated and it brought FRL to the edge of bankruptcy to meet the contract deadline. The commander of SAC, General Curtis LeMay, was only interested in a system that could refuel bombers and Boeing's flying boom was his method of choice. FRL needed another demonstration of the advantages that their probe and drogue could give to jet fighters and the opportunity was not long in coming.

Back in July 1948 the USAF had deployed 16 F-80 Shooting Star jet fighters across the Atlantic from Selfridge AFB in Michigan to RAF Odiham. This was Operation "Fox Able One" (Fighters Atlantic One) and the movement took 10 days staging via Bangor, Goose Bay, Greenland, Iceland and Stornaway. In May 1949 "Fox Able Two" took 16 days over a similar route. USAF Col David Shilling had led "Fox Able One" and was very interested in any way that the deployment of jet fighters could be improved upon. The outbreak of war in Korea on the 25th June gave added urgency to finding a solution. At the 1950 SBAC Display at Farnborough he witnessed the first public demonstration of probe and drogue refuelling between FRL's Lincoln tanker and Meteor Mk 4 flown by Marks and Hornidge. In a novel experiment the R/T was relayed over the public address system. However, Hornidge's expletives when fuel washed over the Meteor's canopy on disconnect were heard by all! Col Schilling realised that probe and drogue solved the fighter deployment problem and was aware that two F-84s had been converted by FRL as receivers with wing mounted probes. He was granted authority to make an attempt at a non-stop flight refuelled crossing of the Atlantic by the F-84s.

The plan was to fly the pair of fighters from Manston to Mitchell Field in New York, refuelling from Lincoln and KB-29 tankers over Prestwick, Keflavik and Goose Bay. The first attempt "Fox Able Three" took place on the 19th September 1950 but was aborted after Schilling made the first contact and found that the Lincoln's HDU was malfunctioning. It was just as well since the Keflevik based Lincoln tanker had suffered a fire after take off and had to have an engine replaced. A second attempt, "Fox Able Four", was made on the 22nd September. The first RV went well but poor weather over Iceland led to problems joining up with the second Lincoln tanker. Practical RV techniques had yet to evolve and too much reliance was put on a special radar in the FRL tanker. Eventually it was agreed that the Lincoln and F-84s would orbit in the cone of silence from Keflevik radio until they were visual. Schilling made a successful contact but Col Bill Ritchie in the second F-84 had a problem. The refuelling probes fitted to the F-84s had a manually operated valve that had to be opened by the pilot after contact and closed before disconnect. Ritchie disconnected before the valve closed and damaged his probe. Despite this they decided to press on for the third tanker, the KB-29, near Goose Bay. Schilling and Ritchie encountered strong headwinds on the next stage and became tanker dependent before reaching Goose. Ritchie found he was unable to take on fuel with his damaged probe so he decided to climb for height and glide for Goose Bay before he flamed out. He broke out of cloud at 12,000 ft, over Lake Melville, 40 miles from the airfield. He was still 30 miles short when his engine died and after passing a message to his wife via Schilling he ejected at 3,000 ft. Schilling continued to make a landing in the US at Limestone (Loring) AFB in Maine after a flight time of 10 hours and 8 mins! Ritchie was rescued by helicopter after landing in a tree.

Despite the partial failure of the flight, "Fox Able Four" was a transatlantic first for jets and proved that the flight-refuelled deployment was practical. The lessons learned led to the development of an automatic probe valve. The Farnborough demonstration and the publicity surrounding "Fox Able Four" finally provoked the British Air Ministry into taking a closer look at flight refuelling. They decided to convert the 16 Meteor Mk 8 fighters of 245 Squadron, based at RAF Horsham St Faith in Norfolk, to probe receivers for refuelling trials with Lincoln tankers. These trials, code named "Operation Pinnacle", eventually began on the 8th May 1951 and continued until the end of October. Although completely successful, "Pinnacle" failed to convince the Air Staff who considered that the provision of tankers for the RAF would simply mean fewer fighters. This incredibly flawed logic could not be further from the opinion of the USAF who by this time had already used flight refuelling in combat!

By spring 1951 FRL had completed the conversion of the B-29s into a single point KB-29T and a 3-point YKB-29T. The YKB-29T was immediately nicknamed the "Triple Nipple" by the Americans and a demonstration of its capability was arranged. Two probe-equipped Meteor Mk 8s were borrowed from 245 Sqn and with FRL's Meteor Mk 4 made the first simultaneous 3 aircraft refuelling from the "Triple Nipple". The Americans were very impressed. They realised that numbers of fighters was not a factor when their targets in Korea were out of jet range from their bases in Japan. Flight refuelling would solve the problem and in June 1951 the single point KB-29T was flown to Yokota AB, Japan and attached to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing. There wasn't time to convert enough jet fighters to single point probe refuelling but USAF engineers at Wright Patterson AFB in Ohio came up with a solution. By fitting probes to their drop tanks the fighters did not need the additional internal plumbing which FRL had found so difficult with the F-84s. Lockheed, Republic and North American were tasked with converting the tanks on the F-80 Shooting Star, F-84 Thunderjet and F-86 Sabre. The swept wing and underwing tanks of the F-86 proved to be unsuitable but the straight wing and tip tanks on the F-80 and 84 gave no problems and conversions were soon underway. The refuelling technique required three contacts to avoid fuel asymmetry. The left tank would be half filled, then the right filled to full before the receiver topping up the left again. It was far from ideal but in the time available it was an acceptable system.

The program was code named "Project Collins" and culminated in the first flight refuelled combat mission in history on the 6th July 1951. Three RF-80As took off from Taegu in South Korea and rendevoused with the KB-29T tanker off Wonsan, North Korea. It was 210 nm from Taegu to Wonsan and the RF-80A had a range of 330 nm. After refuelling the 3 RF-80As were able to use their full range to photograph targets in the far north of Korea. At 0510 hours on the 28th September 1951 Major Harry Dorris took off from Japan in his F-80A, armed with a full war load of bombs, rockets and guns. He refuelled 8 times from the KB-29T tanker, between which he carried out a series of low level strikes on targets in North Korea before landing back in Japan at 1925 hours. He had established a new endurance record for jet aircraft of 14 hours and 25 minutes and done it under combat conditions!

The USAF now began a full-scale flight refuelling operation over Korea code named project "High Tide". Ten KB-29M looped hose tankers were released from SAC for conversion to a "quickie fit" probe and drogue tanker by FRL. Even the "Triple Nipple" got in on the act and was deployed to Japan. "High Tide" initially involved three F-84 squadrons of the 136th FBW, which were converted with tip tank probes for an operational test of large tactical units using flight refuelling. The program had three phases; training the 3 squadrons, establishing combat air patrols over Japan and finally carrying out strikes on North Korea. A number of units took part in "High Tide" including the Air National Guard squadrons of the 116th FBW. "High Tide" culminated on the 29th may 1952 when 12 F-84Es of the 159th FBW flew from Japan to carry out successful full scale ground attack strikes on North Korea, refuelling en-route from the KB-29T tankers. The USAF concluded from "High Tide" that although the wing tip refuelling had been a success it was only an ad hoc emergency substitute for a single point system. However, the value of flight refuelling to tactical aircraft operations was undisputed. Probe and drogue was now combat proven and the system of choice for tactical aircraft. However, the battle with the boom was far from over, indeed it had hardly begun.

Part: 5

The Battle of the Boom.

It had taken just three years for the probe and drogue AAR system to progress from Peter MacGregor's drawing board to use in combat during the Korean War. Although the RAF continued to disregard the advantages of AAR, the Project "High Tide" trials convinced the USAF that in-flight refuelling not only had a vital role with SAC's nuclear bomber force but also was of significant value in tactical and theatre jet operations. However, the question remained as to which AAR system the USAF should adopt, either the now combat proven (but British) FRL probe and drogue, or the All-American Boeing flying boom. Boeing had been working on their boom system since November 1947 and it must have been galling for their engineers to watch the rival probe and drogue system see action first. However, the Boeing boys had powerful support for the boom from SAC commander-in-chief, General Curtis Le May, who saw the boom tanker as his own pet project. In March 1950 the first of 116 KB-29P boom tankers entered service with SAC and by December that year Boeing had converted the first C-97 Stratocruiser with an improved boom. The first KC-97E boom tanker entered service with the 306th Air Refuelling Squadron at McDill AFB, Florida, on the 14th July 1951 and eventually 814 KC-97 boom tankers would be built for SAC by Boeing.

Although the USAF had been able to rush probe and drogue tankers into combat over Korea, the job of converting the relatively complex American jet fighters like the F-84E as single point probe receivers had proved to be more difficult than expected. The initial contract had almost driven FRL to bankruptcy and forced Cobham to sell the probe and drogue manufacturing rights to the Americans. The USAF engineers' interim solution of twin tip-tank probes worked after a fashion but required pilots to make 3 separate contacts per onload to ensure fuel asymmetry was kept within limits. In 1951 Republic Aviation, who built the F-84 Thunderjet, began production of the F-84G model with a redesigned fuel system for single point refuelling. The F-84G was the first single seat fighter-bomber with the ability to carry nuclear weapons. It was equipped as an AAR receiver to enable it to carry out long range missions as part of the SAC nuclear strike force. However, Republic had not opted for a probe but had fitted a boom receptacle in the leading edge of the left wing. SAC's rapidly growing fleet of boom tankers and pressure from Le May undoubtedly influenced this decision.

On July 4 1952, sixty F-84Gs of SAC's 31st Fighter Wing took off from Turner AFB, Georgia, and 1,800 NM non-stop to Travis AFB, near San Francisco, California. They were refuelled over Texas by 24 KB-29P boom tankers. This operation was a dress rehearsal for Fox Peter One (Fighters Pacific One), the transpacific movement with AAR support of all three squadrons of the 31st FW to Japan.

The Fox Peter One deployment was led by Co, David Schilling, the pioneer of the first transatlantic AAR trail in 1950, Fox Able Four, which used the probe and drogue technique. The plan was for the F-84s to be refuelled on the long 1.860 NM leg from California to Hawaii and then island hop via Midway, Wake, Eniwetok, Guam and Iwo Jima to their destination, Misawa and Chitose Air bases in Japan. KB-29P tankers would orbit at 18,000 ft in position over Weather Station Alpha with 6 backup tankers over Weahter Station Uncle a few hundered miles east of Hawaii. The first Squadron crossed on 6th July 1952 followed by the other two waves on subsequent days. All the F-84Gs arrived in Japan on the 16th July, just 12 days after leaving Georgia. The crossing was substantially faster than the time taken to disassemble the aircraft and ship them across the Pacific as deck cargo, which had been the only option up till then. On the 29th July the first non-stop jet crossing of the Pacific was made by an RB-45C Tornado flying from Elmendorf AFB, Alaska to Yokota AB in Japan. The Tornado jet bomber was refuelled twice by KB-29P boom tankers. Both this crossing and the Fox Peter One deployment were intended to give the Soviet Union notice of the new USAF rapid reinforcement capability bought about by AAR. In October "Fox Peter Two" saw the F-84Gs of the 27th Fighter Escort Wing make the crossing and transpacific "Fox Peter" movements became routine in 1953.

It is interesting to note that despite the growing force of Boeing boom tankers, there were still numbers of KB-29M tankers using FRL's looped hose system in service with SAC. Indeed in December 1952 60 aircraft of the 301st Bomber Wing deployed to RAF Brize Norton on 90 days TDY, including 15 KB-29M looped hose tankers. These were the first AAR tankers to operate from RAF Brize Norton, which must be one of the few air bases in the world to have seen all three AAR systems in operational service!

As the more capable KC-97 boom tanker began to enter service in numbers the USAF's ability to mount routine transoceanic deployments began to be exploited more fully. On the 20th August 1953 SAC carried out Operation Longstride, a double transatlantic deployment of 28 nuclear capable F-84G Thunderjets from Turner AFB to bases in the UK and North Africa. Once again Col Schilling led the first wave of 8 fighters from the 31st Fighter Escort Wing, flying 3,800 NM via KC-97 refuelling tracks over Bermuda and the Azores, to land at Nouasseur AB in French Morocco 10 hours and 20 minutes later. The second wave of 20 F-84Gs from the 508th Fighter Escort Wing, led by Col Thayer S Olds, took off a few minutes after Schilling and refuelled 3 times from KC-97s over Boston, Goose Bay and Keflavik. Three fighters diverted into Keflavik but 17 landed at RAF Lakenheath, 11 hours and 20 minutes after leaving Georgia. Operation Longstride showed just how far AAR deployment techniques had progressed since Col Schilling made his first crossing in 1950.

As capable as the KC-97s were, they were hard pressed to match the performance of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet bombers now entering service. To refuel from the KC-97 the B-47 had to descend from 35,000 ft to 18,000 ft where it could begin to tank. As the B-47 filled and got heavier the KC-97 would have to enter a shallow "toboggan" decent to keep the bomber in contact and could go as low as 12,000 ft. The B-47 would then have to use half of the fuel it had just received just to climb back to its cruising altitude. The SAC bomber crews considered the "toboggan" manoeuvre with the KC-97's flying boom to be difficult at the best of times and potentially dangerous in poor weather conditions. Clearly the solution was to have a jet tanker with similar performance to the Stratojet bomber.

The quickest and easiest solution was to fit a B-47 with a HDU in its bomb bay for probe and drogue tanking. Early in 1953 the USAF engineers at Wright-Patterson AFB converted two B-47s for probe and drogue trials, the tanker becoming a KB-47G and the receiver a YB-47F. Considering it was a cheap "off the shelf" solution the KB-47G was a good tanker. Fitted with bomb bay tanks it could carry 59 tonnes of fuel, which gave it an AAR capability similar to the much later RAF Victor K2 tanker. To many in the USAF at the time, probe and drogue had a number of significant advantages over the Boeing flying boom. It was simpler, lighter and cheaper than the boom and imposed much less aerodynamic drag for the tanker making it more fuel-efficient. Its simple operation did not require the specialist skilled boomer of the Boeing system and there was potential to rapidly modify a fleet of KB-47 jet tankers to support SAC's new B-52 Stratofortresses about to enter service. However, although the KB-47G tanker and YB-47F receiver made the first jet to jet AAR contact on 1st September 1953 and the trials proved that the system could be used successfully by the B-47, it did nothing to change General Le May's prejudices against probe and drogue.

Le May believed that his pilots would have great difficulties controlling the sluggish 200 tonne mass of a B-52 while making contact with a small and unstable drogue and also considered that rubber hoses would be unreliable in the low temperatures above 30,000ft. Although these problems proved to be generally unfounded the boom did enjoy one undeniable advantage over a hose system. The wider pipe diameter of the boom would always transfer fuel faster than the smaller hose if the receiver were capable of taking it at the higher rate. The optimum transfer rate of the probe and drogue system at the time was 250 gallons a minute but the boom could pass 700 gallons per minute. However, the boom-equipped tankers could only refuel one aircraft at a time whereas the "Triple Nipple" probe and drogue tanker had refuelled 3 fighters at once. Also the tactical fighters could not take on fuel at the full rate of the boom system.

In February 1953 the USAF carried out a fly-off trial between the flying boom and probe and drogue tankers at Offutt AFB, Nebraska. A single KC-97 was fitted with a HDU for the trial and a variety of aircraft equipped as probe receivers. The outcome of the trial between the two systems was entirely predictable. Fighter pilots preferred probe and drogue while the bombers opted for the boom. The trouble was that all the tankers belonged to SAC, which was General Le May's train set. Unsurprisingly, the Boeing test pilots that carried out the trials considered that the probe and drogue would be unsuitable for use by the B-52. SAC also preferred the KC-97 to the KB-47 because the converted transport could also be used to deploy personnel and equipment to its overseas bases. The Boeing lobby prevailed and SAC went with the flying boom. As far as Le May and SAC were concerned the battle of the boom was over. The probe and drogue had lost and the system would have no place in SAC's growing tanker force. However, outside SAC General Le May's opinions held less sway. Already plans were being made for rival probe and drogue tanker fleets in USAF Tactical Air Command and the US Navy, and across the Atlantic the RAF began to realise that they could no longer ignore AAR in their future plans. Probe and drogue was just too good to fade away.

Part: 6

Tankers Aweigh!

When SAC, the progenitors of military AAR, committed its growing fleet of tankers to the Boeing flying boom system there appeared to be little future for the probe and drogue technique within the USAF. SAC's maverick commander, General Curtis Le May, had ordered over 800 of the piston engined Boeing KC-97 boom tankers and its planned jet replacement would also be equipped solely with the Boeing system. With the Cold War nuclear bomber force dominating USAF doctrine for the foreseeable future, the tactical airpower lessons of the Korean War were soon forgotten or ignored by the air force.

However, it was the USAF's rival in global airpower, the US Navy, that would next embrace probe and drogue AAR and go on to become its greatest champion. US Naval Aviation had suffered a severe blow to its strategic plan when the giant 100,000 ton aircraft carrier USS United States was cancelled in April 1949. The large Neptune atomic bombers intended for the carrier were forced to languish ashore and the US Navy's nuclear aspirations were in disarray. When the Korean War broke out the US Navy entered the fray with 30,000 ton straight decked WWII carriers, which soon proved impractical for intensive jet operations. The early Navy jets were underpowered and thirsty. The weights that allowed safe carrier take-offs and landings left them with only a small margine for weapons and fuel, which limited their mission flexibility and left them vulnerable to attack by Communist Mig15 fighters. After initial carrier deployments of Grumman F9F-2 Panthers jets in July 1950, it was piston engined types such as the AD-4 Skyraiders and F4U Corsairs that were to dominate US navy flight decks throughout the conflict.

By 1950 it was clear that jets would get much bigger and faster and to operate them successfully at sea would require nothing short of a revolution in aircraft carrier design. Ironically it was the British, the poor relations to American naval power, that would provide the technical answers and lay the foundations of the fleet of US Navy supercarriers that exist today. Despite the severe economic restrictions after WWII the Royal Navy had embarked on an intensive R&D programme aimed at solving the problems of carrier jet operations. Initially, much money and effort was spent on developing a flexible rubber flight deck that would allow jets to land without undercarriage but this concept was a technological dead end. A more practical development was the powerful steam catapult first installed on HMS Perseus in 1951. This allowed faster launch speeds at much heavier weights than before. The second great breakthrough was the angled flight deck, first suggested on the 7th August 1951 by Captain Denis Campbell at a Ministry of Aviation conference on methods of using the flexible flight deck. This innovation immediately eliminated the danger of a catastrophic crash into parked aircraft if a jet missed the arrester cable. The third development was Lt Cdr Nick Goodhart's gyro-stabilised mirror landing system. At higher jet landing speeds there was too much lag in the WWII system of hand signals from a "DLCO" on the flight deck. The mirror sight allowed pilots to monitor their own approach and react promptly to deviations in the flight path. The combination of steam catapult, angled deck and mirror landing sight made carrier operations by high performance jets possible. However, it was another British development that would help make carrier jet operations a practical military proposition.

The US Navy was aware of the USAF's tactical AAR trials over Korea in 1951 and saw this as a solution to the weight limitations, which would always be a factor of carrier operations. It was clear that probe and drogue was the only system the US Navy could use, as a boom tanker would be far too large for any carrier. In June 1952 a North American AJ-1 Savage bomber was fitted with a FR Inc A-12 HDU in its bomb bay to become the first carrier borne tanker. An F9F-2 Panther jet was fitted with a probe for trials which demonstrated the advantages of AAR to naval aviation. The Savage tankers first deployed to sea with VC-9 on the USS Midway in 1953. Now more take off weight could be dedicated to weapon loads with aircraft topping up from the tankers orbiting over the carrier before proceeding on their missions. The tankers could also help aircraft recovering to the carrier short of fuel to prevent them from diverting to airfields ashore. AAR also vastly increased the range and endurance of carrier based jets to a much larger degree than land based aircraft. The US Navy began a program to equip a number of jet fighter types with refuelling probes and carried out demonstrations of the advantages it had gained. On the 1st April 1954 the first USA transcontinental flight in less than 4 hours was made by three pilots of VF-21 in F9F Cougars in a 2,438-mile flight from San Diego to New York, refuelling from AJ-1 Savage tankers over Kansas. These successful trials and demonstrations convinced to US Navy that probe and drogue AAR was a vital element in the future of naval airpower. On the 1st September 1955 the US Navy announced that all naval fighters in production would be fitted with probes for in-flight refuelling, establishing the technique as a standard operational procedure.

One of the most impressive tanker aircraft ever produced was the US Navy's huge Convair R3Y-2 Tradewind 4-engined turboprop flying boat transport. It was equipped with four wing mounted HDUs and became the first (and only) tanker to simultaneously refuel 4 aircraft, US Navy Grumman Cougar jet fighters, in September 1956. However, this enormous tanker was of little use to carrier air wings operating far from shore and even the KAJ-1 Savage was too large to operate from most US Navy carriers in the early 1950s. To provide an on board AAR capability until the new supercarriers of the Forrestal class entered service the Douglas aircraft company developed the D-704 refuelling pod which was initially carried by the AD-6 Skyraider but could be fitted to any carrier aircraft turning it into a "buddy-buddy" tanker. The D-704 pod represented the biggest advance in AAR since the invention of probe and drogue. When the tiny nuclear capable A4D-2 Skyhawk entered service in 1957 "buddy-buddy" tanking gave it a range of almost 2,000 miles and gave the US Navy a nuclear delivery system easily able to operate from any of its carriers. The US Navy regained a strategic strike role it had thought lost since the cancellation of the USS United States.

The US Navy had the resources and the enthusiasm to rapidly adopt all the British innovations in naval aviation and by 1957 it had converted most of its existing carriers to the new design as well as commissioning a fleet of new large jet supercarriers. The Royal Navy, on the other hand, had been constrained by British economic difficulties and could only convert four relatively small WWII designed carriers to modern jet operations. With their much smaller aircraft complement the RN carrier wings would clearly benefit from significant force multiplication if they adopted "buddy-buddy" AAR. In 1958 FRL developed the Mk 20 refuelling pod for use with the Supermarine Scimitars and DeHavilland Sea Vixens about to enter RN service. The new jets quickly obtained their receiver clearance after tanking from a Canberra equipped with the new pod. In 1961 Mk 20 pods were delivered to 899 Sqn at FAA Yeovilton for use with their Sea Vixens which became the first RN tankers. 899 Sqn were able to demonstrate "buddy-buddy" tanking at the 1961 Farnborough air show, just a week after the delivery of their first Mk 20 pods. Following the US navy lead the Blackburn Buccaneer incorporated an AAR probe at an early stage of its design. The initial retractable probe was replaced by a fixed probe after trials revealed that the original design disrupted the airflow to the starboard engine. When the Buccaneer S1 entered service with 800 Sqn in 1964 the unit had a dedicated flight (800B Flt) of four Scimitar "buddy-buddy" tankers. Early plans to convert some Buccaneers to tankers called for a Mk 21 HDU pack to be fitted in its bomb bay but this was abandoned in favour of a Mk 20 pod under the starboard wing. The superb Buccaneer retained its secondary "buddy-buddy" tanker role throughout its long RN and RAF service.

The commissioning in the US Navy of the 70,000 ton Forrestal class carriers now enabled much larger and faster jet aircraft to operate at sea. In 1956 the US Navy finally got a long-range jet bomber in the Douglas A-3D Skywarrior. This large and adaptable aircraft would serve in many roles in the US Navy until 1991 and even proved able to operate from the smaller modernised WWII Essex class carriers. Supersonic fighter operations also began with the entry into service of the Vought F8U-1 Crusader. In June and July 1957 US Navy Crusaders made high speed in-flight refuelled transcontinental flights culminating in Project Bullet on the 16th July when Marine Major John Glenn flew his Crusader from Los Angeles to New York at an average speed of Mach 1.1. Glenn and his wingman, Lt Cdr Charles Demmler, refuelled en-route from a piston engined Savage tanker, but the high performance Crusader had problems at the Savage's slow refuelling speed and Demmler damaged his probe forcing him to abandon his attempt. By the early 1960s the faster jet Skywarrior had replaced the Savage in the AAR tanker role and was capable of lifting a 10 tonne fuel offload. The Skywarrior tankers would prove to be a vital asset for the US Navy. The importance of AAR was about to be conclusively demonstrated during air operations over a little known Asian country called Vietnam and for the second time probe and drogue would be used in combat.

Part: 7

The TAC Tankers.

The US Navy's rapid adoption of probe and drogue AAR kept the system alive and secured its development in the face of SAC's overwhelming championing of the flying boom. However Tactical Air Command, the USAF's second combat arm, had been the instigators of the Project "High Tide" combat trails over Korea and recognised the many advantages that AAR offered tactical airpower. The SAC tanker force was growing rapidly with over 800 KC-97 entering service and over 700 of the revolutionary Boeing KC-135 jet tankers on order from 1954. Unfortunately these were dedicated almost exclusively to supporting SAC's expanding force of B-47 and B-52 nuclear bombers. After Korea the concept of all out nuclear warfare dominated USAF doctrine and its senior commanders critically undervalued the role of tactical forces, a factor that would cost dearly in the Vietnam conflict. If TAC were to fully exploit the advantages of AAR it would have to get its own dedicated fleet of tankers.

The new "Century Series" of tactical fighters, the F-100, F-101, F-104 and F-105, were all equipped with refuelling probes. The F-105 Thunderchief actually had both a retractable probe and a boom receptacle due to its original development as an escort fighter for SAC bombers. To service these aircraft TAC initially looked to the KB-47 Statojet tanker originally converted for the 1953 probe and drogue trials. The KB-47 would have been an excellent probe and drogue tanker, able to fly at fast jet deployment heights and speeds and carrying a respectable fuel load in bomb bay tanks. On July 23, 1956, the USAF authorised the development of a KB-47 two-drogue prototype tanker. However, the cost of the KB-47 conversion promised to be excessively high and SAC was reluctant to release sufficient airframes from its bomber force. The USAF cancelled the KB-47 program on July 11, 1957.

TAC was left with converting the B-50D piston engined bombers that had been replaced by the B-47 in SAC's strike force. Plenty of B-50D and TB-50H airframes were available but they were too slow for modern fighters and had performance problems at the high take-off weights required for world wide tanker operations. To equip the KB-50s as tankers it was decided to use the 3-hose system of the original "Tripple Nipple" KB-29 converted by FRL and used successfully in Korea. The KB-50 was fitted with a Mk 12 HDU in the tail and two further Mk 12 HDUs in wingtip pods. Each HDU had a 75-ft hose and could transfer up to 1,000 kgs per minute. The KB-50's piston engines were fed with AVGAS from its five wing tanks and it carried 13,000 kg of JP-4 jet fuel in its bomb bay tanks. An additional further 3,500 kgs of JP-4 could be uplifted in its centre wing tank. At that time the total internal and external fuel capacity of an F-100 was just 5,000 kg so a single KB-50 was easily capable of giving a 50% top up to a flight of 6 fully armed F-100s. The widely spaced HDU fit also enabled 3 fighters to refuel simultaneously, albeit at a reduced flow rate. As the photographs show, it was quite routine for the TAC KB-50s to refuel fighters and tactical bombers three at a time.

In 1956 the Hayes Aircraft Corporation of Birmingham, Alabama, began converting 136 TB-50D, TB-50 and TB-50H into KB-50 tankers, the first of which entered service with TAC in 1957. To solve the speed and performance problems the KB-50s were fitted with two auxiliary 5,200 LB thrust GE J47 turbojets, which allowed an increase in cruising speed for tanking from 230kts to 300kts at 25,000 ft and greatly assisted take-off performance. The jet assisted KB-50J first flew in December 1957 and entered service with TAC early the following year. With a fleet of KB-50Js gave TAC the ability to deploy its aircraft between theatres. KB-50J tankers based at Bermuda and Lajes enabled TAC fighters to rapidly deploy to NATO bases in France and Germany via the safer southern transatlantic route rather than risky staging operations via Goose Bay, Greenland and Iceland. Transpacific deployments to Japan and Okinawa took place via Hawaii and Wake Island. The tactical role of the KB-50J saw numbers employed with both the USAFE in Europe and with PACAF in the Far East where the KB-50J's ability to operate from the shorter runways at TAC airfields gave it an advantage over the heavier KC-135.

The KB-50J was never more than a short-term solution to TAC's AAR requirements. Although the last B-50 had come off the production line in 1953, the 1940s wartime design was worn out and suffering from fatigue and corrosion by the early 1960s. TAC cast envious eyes on SAC's growing fleet of new KC-135 tankers. By 1961 SAC possessed a fleet of 1, 095 tankers to support its bombers and the USAF decided it would have to share its ample assets with TAC. In exchange SAC would gain control of all future USAF tankers including the planned fleet of 620 KC-135s, 32 squadrons in all. On the 17th November 1961 the deal was done and TAC was promised that at least one wing of SAC KC-135s, about 70 aircraft, would be available for its use if required. TAC's probe and drogue jets would have to get used to refuelling from the Boom Drogue Adapter (BDA) used by the KC-135s.

The last few TAC dedicated KB-50Js served in the PACAF with the 421st ARS, based at Yokota, Japan. However, the KB-50J has one claim to glory, it was the first tanker to see use in the Vietnam War. In May 1964 the United States began flying low level reconnaissance missions with USAF RF-101 and US Navy RF-8 jets over the Plain of Jars in Laos in order to trace the North Vietnamese infiltration routes into South Vietnam. This was the period before formal US involvement in the fighting and PACAF had very few assets available to it. On the 6th June a US Navy F-8 Crusader was shot down over Laos and the US government decided to retaliate with air strikes against communist Pathet Lao anti-aircraft sites. The Plain of Jars strike was flown on the 9th June using 8 F-100D Supersabres and an RF-101 pathfinder flown from Da Nang and these were refuelled by four KB-50J tankers from the 421st ARS deployed in the Philippines. At the time this was considered an isolated event but just two months later the Gulf of Tonkin incident would lead to full involvement of the US military in the growing Vietnam conflict. SAC KC-135s began to arrive in theatre in August 1964 and an initial deployment of 6 tankers would grow to a peak of 172 KC-135s in 1972.

The last KB-50J, the last USAF pure probe and drogue tanker, was retired from the 421st ARS in January 1965. Deemed too corroded to fly back to the USA for scrapping, most KB-50Js were allowed to rot on the fire dumps in at their home bases. Their jet engines were removed and fitted to ex-SAC KC-97 boom tankers that were now relegated to service with the Air National Guard. With the passing of the KB-50s the three-point AAR tanker, which had been proven in combat over Korea and now Vietnam, would not be seen in USAF service again for almost 30 years. It would be the RAF, belatedly adopting AAR in 1958, who would next put a "Triple Nipple" tanker into service.

Part 8.

V is for Tanker.

The first decade of probe and drogue AAR saw its successful use in combat during the Korean war and growing fleets of airborne tankers entering service with the armed forces of the United States. 136 Boeing B-50 bombers were being converted into three point KB-50 tankers for the USAF Tactical Air Command and Douglas KA-3B twin jet tankers were serving aboard the new class of 70,000 ton US Navy aircraft carriers. The British invention was paying enormous dividends in the rapid development of American military and naval aviation in the 1950s.

The British Air Ministry's 1947 assertion that in-flight refuelling was "not a paying proposition" was proving to be a ludicrously unimaginative policy and by the mid 1950s even their "Airships" in Whitehall had to take notice of the emerging role of AAR in modern airpower. Whether it was the rapid growth of Strategic Air Command's tanker forces or the steady bombardment of lobbying letters from Sir Alan Cobham that finally changed the minds of the AAR "Luddites" in the RAF is not known. However, by January 1954 the Air Staff had decided that most of the Valiant and all the Vulcan and Victor bombers on order for the RAF's nuclear "V" Force should be capable of flight refuelling.

Bomber Command's tactical doctrine in the early 1950's differed little from that used against Germany in 1945. Indeed the Valiant and Canberra air raids on Egypt during the Suez crisis in 1956 still relied on pathfinder marking and bombing techniques used by Lancaster crews a decade earlier. The Air Staff realised that the nuclear "V" Force would have to use completely different tactics and procedures which would inevitably be modelled on those of the much larger and more experienced Strategic Air Command. SAC's heavy reliance on AAR to carry out its mission must have influenced the RAF to change its opinion on flight refuelling.

The RAF's flight refuelling requirement differed from the Americans'. SAC's B-52 bombers could not reach their targets from the USA without AAR whereas the RAF's new "V" bombers had the range to reach their targets directly from the UK at high altitude. RAF and USAF aircraft had been able to fly unmolested at high level over the Soviet Union for some years on secret reconnaissance missions and many hoped that the high performance of the "V" bombers would be enough to get them through. However, as the Soviet air defences grew in sophistication and capability it became clear that performance alone would not be enough. The "V" bombers would now need to carry heavy ECM jammers and be able to out-flank the Russian fighter and missile bases protecting their target areas. A flight refuelling capability offered solutions to the increased AUW and range problems that the "V" Force was bound to encounter as it developed.

Despite the Air Staff's new commitment to AAR no mention was made of a dedicated tanker force. In April 1955 it was vaguely hoped that all Vulcans and Victors would be equipped for rapid conversion from bombers to tankers as required. However, Bomber Command was reluctant to release any of its aircraft from its Main Force for use as tankers and ordering additional aircraft for the role was unacceptable. The question of a tanker force for the RAF remained unanswered until early 1957 when a plan for the future composition of the "V" Force envisaged a fleet of 184 bombers made up of 120 Mk 2 Vulcans/Victors, 40 Mk 1 Vulcans/Victors and 24 Valiants. No aircraft were set aside specifically as tankers but it was intended that as the Mk 1 Vulcans and Valiants were withdrawn from the Main Force they could be converted to tankers. 32 sets of bomb-bay tanks had been ordered for the Valiants for delivery in March 1958 and Vulcans were to be equipped with tanker fittings from the 26th aircraft on the production line. At the time there was no intention for the Victor to be used as a tanker, surprising in the light of future developments.

During 1957 the difficulty for those responsible for planning the future size and composition of the "V" Force was the necessity to maintain a large strike force to guarantee that a significant percentage would penetrate Soviet defences. Most of the Mk 1 "V" bombers were allocated to fringe targets in support of the deep strike Mk 2 aircraft and few would be available for use as tankers. Many had underestimated the problems involved in developing an effective flight refuelling capability within existing resources. The Treasury doubted that the RAF fully understood what the future size, composition and operating methods of the "V" Force would be and were strongly against additional funds for tankers. The future of AAR in the RAF hung in the balance.

The situation was clarified in a note from the VCAS, Air Marshal E C Hudleston, to the Air Council on the 6th December 1957. In it he stated that flight refuelling was essential if the "V" Force was to be given the maximum tactical freedom in routing to maintain its viability as a deterrent. In the note the advantages of AAR for the RAF were listed. Bombers could route to avoid heavily defended areas and reduce penetration distances, vital targets beyond normal operating ranges could be attacked and a measure of tactical surprise achieved. The note also envisaged that flight refuelling made possible rapid deployment to overseas bases and avoidance of unfriendly territories en-route. It also enabled the "V" Force to operate from shorter runways and be based beyond the radius of action of an enemy. HQ Bomber Command estimated that a tanker force of four squadrons (32 aircraft) would be required but financial constraints reduced this recommendation to two squadrons of Valiants plus a shadow unit formed by the Valiant OCU.

The Air Council accepted VCAS' recommendations and approached the Treasury for authority to resume work on development of the Valiant tanker. By January 1958 the Treasury had only authorised minimal short-term development work on the Valiant tanker and they would not commit themselves to funding any additional aircraft for a tanker force. In November 1958 they insisted that any aircraft used as tankers should be found within the approved "V" Force establishment of 144 bombers and they would only sanction further development of the Valiant if the Air Ministry agreed not to develop the Vulcan or Victor in the tanker role. The Air Ministry could not accept any reduction in the 144 Vulcan and Victor bombers they considered the minimum to provide a viable deterrent force and they pressed the Treasury for approval to retain additional Valiants as tankers. To promote their case they stated in January 1959 that the tankers would not only be used just to support "V" Force operations but would also be essential in overseas deployments and reinforcements by Fighter Command and tactical transport aircraft.

Again the Treasury prevaricated and in April 1959 letters were exchanged between ministers. Once again the RAF's case for tankers was put, this time adding the advantages that AAR would bring to the new Lightning and TSR2 aircraft in development and requesting funding for two squadrons of Valiants. However, the potential size of the RAF's AAR commitment now alarmed the Treasury who, with incredibly convoluted logic, considered that it would be too much for just 16 Valiants and that this was just the thin end of a wedge of further expenditure for a much larger tanker force. If this were required then the Air Ministry would have to find further cuts to compensate. The MoD quickly replied that, while it could not guarantee that more tankers would not be needed in the future, there were no plans at present to go beyond the 16 Valiants requested. Finally, on the 27th April 1959 the Treasury approved the establishment of a 16 Valiant tanker force as an addition to the 144 "V" bombers in the Main Force. They stated that this would add £2.8 million a year to Bomber Command's running costs and asked the RAF to consider reducing the number of its aircraft equipped as receivers so "they might bear a closer relation to the size of the tanker force."

Thus it was that, just over ten years since probe and drogue AAR was first demonstrated by FRL, the RAF finally gained approval for a fleet of tankers. For more than a decade the British had argued over the costs of AAR with little regard to the proven benefits. The 16 Valiants authorised appear laughably inadequate when set against over 1,600 tankers in service or on order for the USAF at the time, but it was a start. Now the RAF had to put flight refuelling theory into practice, indeed the work had already begun.

Part: 9

Valiant Efforts.

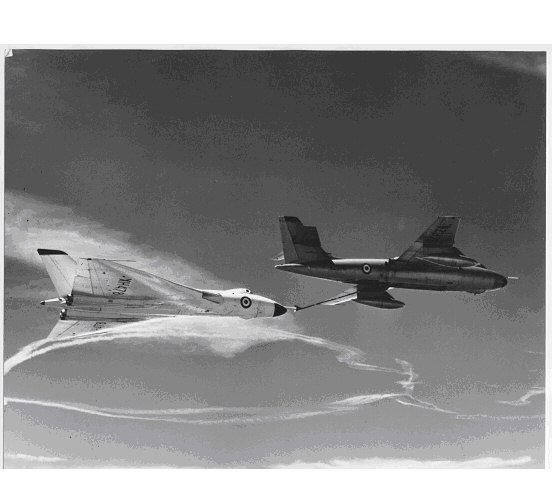

As the Air Ministry and the Treasury bickered over the cost and composition of the RAF's AAR tanker requirement the engineers and aircrews worked at developing the hardware. After the Air Staff's initial dismissal of in-flight refuelling as a waste of money and resources, they began to see the light as early as 1952 and gave FRL the go-ahead for initial AAR design studies for the V-Force. Flight trials began again in May 1953 when Canberra B2, WH734, was loaned to FRL. It was equipped with the prototype Mk 16 HDU being developed for use on the Valiant and became the first British jet tanker. In early 1954 the single prototype Vickers Valiant B2 undertook formation trials with the Canberra HDU tanker and in 1955 the first British all jet in-flight refuelling was carried out between the Canberra and one of the Meteor F8s from the 1951 RAF fighter AAR trials. Later that year a Gloster Javelin FAW4 was fitted with a wing-mounted probe and flew some inconclusive dry contact trials with the Canberra tanker. In later trials the Javelin FAW9 was equipped with a longer fuselage-mounted probe that proved more successful. A production Valiant B1, WZ376, was fitted with the Mk 16 HDU in 1956 and began flying a series of AAR trials from A&AEE Boscombe Down. The first Valiant-Valiant trials began in 1957 and by February 1958 the Valiant tanker and receiver were granted an official release to service for day and night AAR.

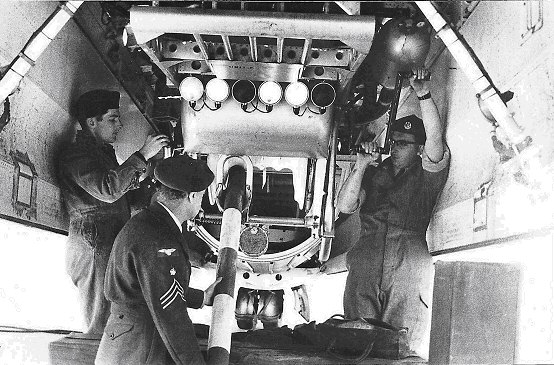

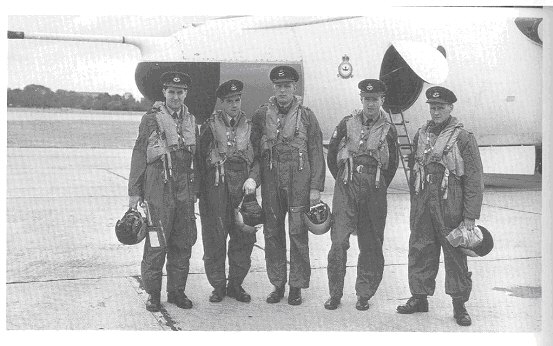

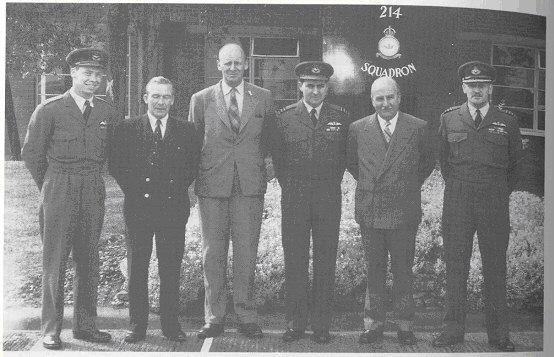

In December 1957 No 214 Sqn at RAF Marham, equipped with Valiant bombers and commanded by Wg Cdr M J Beetham, was selected to carry out the first series of in-service AAR trials. The squadron F540 recorded that preparations were underway to convert the entire squadron to the tanker role, a gloomy and unpopular prospect for the proud bomber crews. In January 1957 the first crews were detached to A&AEE Boscombe Down and FRL's base at Tarrent Rushton on AAR familiarisation courses and in February two 214 Sqn Valiants, WD869 and WD870, completed initial flights equipped with the Mk 16 HDUs. In March 1958 formal trials began codenamed "Trial Numbers 306 and 306A/B". Trial 306 was to test the compatibility of the Valiants tanker and receiver equipment and Trial 306A/B was to develop the initial AAR RV procedures and techniques. The modifications to 214 Sqn's Valiants included the fitting of a nose mounted refuelling probe, installation of the Mk 16 HDU and a 2,000kg fuel tank in the bomb bay, cockpit modifications to the navigator radar's station for a HDU control panel and fitting external flood lights to give a night AAR capability. The modifications allowed the Valiant tanker to transfer up to 20,000kg of fuel at just under 2,000kg a minute. During the initial period of the trial only dry contacts were attempted and there were a few compatibility problems with the Valiant's radar and electrical equipment. Receiver conversion training of the 214 Sqn crews was carried out by Boscombe Down and Vickers test pilots, including Brian Trubshaw who later piloted the prototype Concorde. FRL engineers gave ground instruction. One of the first recommendations of the trial was the establishment of dedicated RAF flight refuelling ground school at Marham, which later became the Air to Air Refuelling School (AARS).

During September 1958 214 Sqn Valiants gave demonstrations of jet aircraft AAR at Farnborough and a number of "Battle of Britain" airshows around the UK. In October a flight refuelling procedures simulator became fully operational at Marham and AAR crew training began in earnest. By January 1959 214 Sqn was ready to begin wet contact trials. From the 26th January to the end of the month four crews carried out 26 day and 17 night wet contacts to prove the system. In February the first of a series of long duration flights using AAR began when Wg Cdr Beetham's crew completed a 12-hour sortie using AAR. When the final treasury approval for an RAF tanker force of 16 Valiants was granted in April 1959, 214 Sqn began a series of highly publicised record breaking long range flights to East Africa. Valiant tankers prepositioned at Malta, Tripoli in Libya and Nairobi and on the 15th April Wg Cdr Beetham and his crew flew a non-stop sortie from Marham to Salisbury (Harare) Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). The distance of 5,320 miles was covered in a record time of 10 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 522 mph. 214 Sqn continued to demonstrate the increased ranges made possible with AAR techniques with record flights by the Beetham crew to Johannesburg in June and to Capetown in July. The London to Capetown flight covered 6,060 miles in 11 hours and 28 minutes at an average speed of 530 mph.

In the autumn of 1959 214 Sqn Valiants began refuelling Vulcan B1As, newly equipped with in-flight refuelling probes. 101 Sqn based at RAF Finningley was the first Vulcan unit to carry out receiver training and the first dry contact was made by Flt Lt W S Green in XA910 on the 28th October. Reports on Trial 306 were published on the 30th November 1959 and this is the date when the RAF officially established an operational AAR capability. Trial 306 was completed on the 25th May 1960 when 214 Sqn Valiant WZ390 was flown flight refuelled non-stop from Marham to Singapore, covering 8,120 miles in 15 hours 35 minutes, the longest point to point flight made by an RAF aircraft up to that time. In June the Gloster Javelin FAW9s of 23 Sqn began receiver training, culminating in August with the RAF's first fast jet AAR trail by Javelins to Akrotiri. In October 1960 four 23 Sqn Javelins were trailed from the UK to Butterworth, Malaya, in five days, via Akrotiri, Bahrain, Mauripur and Gan. In December the Javelins of 64 Sqn and Vulcans of 617 Sqn began their receiver qualification.

Planning went ahead for a spectacular demonstration of the RAF's new global AAR capability involving a non-stop UK to Australia flight by a Vulcan B1A. On the 20th June 1961 nine Valiant tankers of 214 Sqn deployed to Cyprus, Pakistan and Singapore to support the record flight from Scampton to Sydney by a 617 Sqn Vulcan flown by Sqn Ldr Michael Beavis. At this time it was also decided to abandon the RAF Mk 6 probe and drogue and standardise on the NATO Mk 8 system, which was used by the USAF and US Navy probe-equipped aircraft. Joint RAF/USAF exercises demonstrated the Valiant tanker's compatibility with USAF TAC B-66, F-100 and F-101 receivers and even allowed the Valiant to refuel from the piston engined KB-50 tanker.

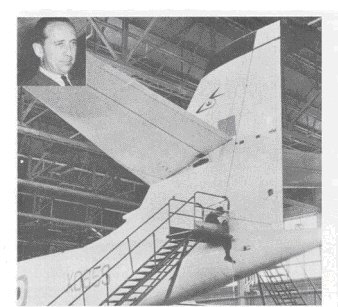

In August 1961 90 Sqn, based at RAF Honington, began training in the tanker role and became as the second operational RAF tanker unit in October. The formation of a third Valiant tanker squadron was proposed to give additional AAR support for the RAF transport force and approval sought from the treasury. However, by this time the operational limitations of the Valiant tanker were becoming apparent. The Valiant's small transferable fuel load and single hose required multiple tankers to support even a single fighter on most trail stages. Also its performance was seen as only marginally compatible with aircraft such as the Lightning and it was thought to have insufficient speed to refuel the TSR2. The crucial shortcoming was that the Valiant's planned fatigue life would only last until 1968 and this alone would dictate its replacement with a more advanced aircraft. Studies began on the conversion of the Handley Page Victor as a tanker and plans for a third tanker squadron were put on hold.

The Valiant tankers of 214 and 90 Sqns continued to support RAF exercises and operations and officially became single role tankers squadrons on the 1st April 1962, finally losing their bomber commitment. The Valiants carried out operational AAR training with 50 Sqn's Vulcans, 57 Sqn's Victors and 56 Sqn's Lightnings as well as the Sea Vixens and Scimitars of the RN FAA. V-Force trials included using the new tanker force to test airborne command post communications with the main bomber force and maintain a continuous airborne alert by Vulcan bombers, which lasted fourteen days! In July 1963 twelve Valiant tankers from 90 and 214 Sqns deployed to Libya, Aden and Gan to support Operation Walkabout, the non-stop flight by three 101 Sqn Vulcan B1As from Waddington to Perth, Australia. In March 1964 tankers from both squadrons trailed four Javelin FAW9Rs from Binbrook to Butterworth, staging via Aden and Gan. The long Indian Ocean legs required very accurate refuelling plans that pushed the capabilities of the single-point Valiants to the limit.

Despite their limitations the Valiant tankers were proving to be an indispensable asset to the RAF and the aircrews of 214 and 90 Sqns completed valuable work in developing the AAR procedures and techniques which are still in use today. All was going well until the discovery in August 1964 of major fatigue cracks in the Valiant's rear spar. At first it was hoped that most of the fleet could be repaired but in early December even bigger cracks were discovered in the front spar and all Valiants were grounded. Investigations showed that 60 out of 61 RAF Valiants suffered from major fatigue damage and it quickly became clear that non of them were safe to fly. The RAF finally announced the withdrawal from service of the Valiant on the 26th January 1965. The crews of 214 Sqn heard that their squadron was to be disbanded on the BBC news as the official signal arrived at RAF Marham after most had gone home. The sudden death of the Valiant force ended seven years of AAR development that had given the RAF a truly global force projection capability for its bombers, fighters and transports. The race was now on to fill the crucial gap left by the withdrawal of the pioneering Valiant tankers. Gary W8man Feb 00

Copyright Feb/00, Author Flt/Lt Gary Weightman

Gary has very kindly given his permission to share the above article with the 214 Squadron website. If you wish to contact the Author regarding this article, please send a note to the site and it will be forwarded on.